*Note: This is a slightly edited version of my keynote address at the first ever Queer Indigenous People of Color Upper Midwest Conference. The talk was ~30 minutes, so it’s a little long. I would love to hear any thoughts you have!

I. Solidarity

We throw around the word solidarity often, especially in QPOC spaces. We talk about standing in solidarity with each other as a necessary sacrifice: of time, resources, energy. We talk about developing an intersectional analysis as a political task that takes away from our daily work but that we understand as essential.

Here’s what I think we miss. Solidarity isn’t actually a sacrifice. Or at least, it shouldn’t be. It’s not something that we should be taking time out of our daily work to do, it shouldn’t feel like an additional burden. If it’s to be effective, solidarity needs to be selfish. Self-serving, self-advancing, and self-interested.

I want to put forward an idea of ‘selfish solidarity.’ This isn’t meant to erase privilege, including within people of color spaces; or to pretend that all our issues are actually the same; or that we have the same investment in every issue. Rather, this is a reframing of how we think and talk about our organizing work, especially in people of color spaces. How we explain our work to our community, how we frame our asks when we want to mobilize. Especially when we are the ones asking others to stand in solidarity, when we are not the most impacted. How would it shift our work if we re-framed our ideas of solidarity as selfish, and really framed standing in solidarity as standing for ourselves?

II. Selfish Solidarity in Political Education: ECSS

I realize this is a little vague so far. Let’s make this concrete with some examples. First, let’s talk about what this idea of ‘selfish solidarity looks like in political education. Then, we’ll move into what this can look like in more on the ground organizing.

I’m going to use an example from work that I’ve been part of for a few years now. Though I’m not helping to organize this year, I was part of a New York collective called East Coast Solidarity Summer and some of its counterparts in other cities for about 4 years.

ECSS, along with BASS in the Bay Area and CDYR in Chicago, is a political education weekend retreat for South Asian youth. In ECSS, youth from all around the East Coast and sometimes the South delve into a politicized understanding of South Asian identity, making visible a history of South Asian resistance to oppression, and creating a distinctly different understanding of what it means to identify as ‘South Asian.’ We spend lots of time talking about the role of South Asians in racial justice movements and in liberatory organizing more broadly.

One of the workshops that has become a standard piece of the ECSS curriculum is Queer & Trans* Liberation. I think that the way we’ve framed this workshop is an example of what it means to educate from a perspective of selfish solidarity.

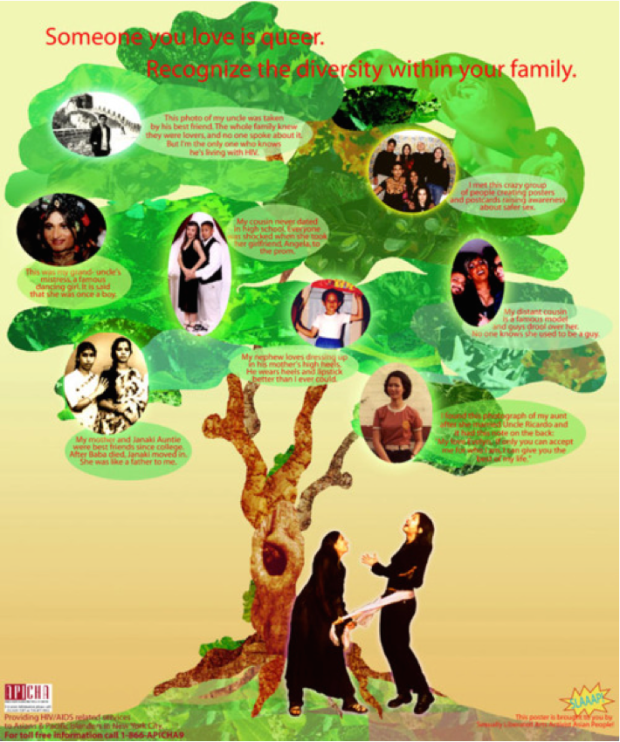

Queer and trans* South Asian bodies are often seen as ‘too westernized,’ ironically no longer part of the model minority because we have succumbed to the seedier sides of American culture, so we’ve become Americanized in the ‘wrong way,’ and have become tainted. ECSS rejects this narrative, and actively reclaims our South Asian legacies of queerness – both because many of our organizers identify as queer, and because we choose to center queerness in our curriculum.

In the Queer & Trans Liberation workshop, we ask participants to name what is at stake for all of us, not just queer and trans people, in sexual and gender liberation. How do all South Asians benefit when queer and trans South Asians are given the space to live full lives? What histories become visible when centering queer and trans* lives is seen as essential to South Asian liberation and racial justice as a whole?

This is at the base of ‘selfish solidarity’ – instead of framing queer and trans* liberation as an important component of allyship, we ask South Asian youth to locate their own investment in breaking down sexual and gendered oppression in the South Asian diaspora. We ask every young person to understand how they are personally impacted by homophobia, and to find their own stake in queer and trans* liberation. We frame solidarity with queer and trans* communities as something that is deeply personal and that is tied to every South Asian person’s ability to be free, whether or not they identify as queer.

So, what has this looked like in the workshops themselves? First, we highlight the often hidden histories of queerness in our communities in South Asia. We interrogate the history of 377 and laws penalizing sodomy in South Asia and India in particular, reminding participants that those laws are actually a colonial British legacy. We remind participants that queerness has always been part of South Asian histories and communities.

The picture above, from a protest in India, is really interesting, because “Quit India” was originally an anti-colonial campaign. This demystifying of South Asian homophobia is incredibly important. South Asians, along with many people of color communities, are told that our people and our cultures are inherently homophobic and transphobic – a convenient invisibilizing of the role of white colonial sexuality policing. Homophobia, seen as quintessentially South Asian, is then used as a justification for portraying South Asia as backwards, both in South Asia and in the U.S.

Reframing homophobia in South Asia as the result of a white colonial legacy is a rewriting of this script, inscribing queerness into the fabric of South Asia and rejecting imperialist narratives that write off South Asians as inherently backwards. This is a political project that every South Asian person has a deeply personal stake in – being seen as full people, not simply as relics of an exotic and backwards culture, is only possible if we reclaim our histories of queerness, and locate homophobia in imperial and colonial legacies.

The myth of inherently homophobic South Asians migrates to the U.S. as well. In diaspora, we are told that our families are culturally conservative, and that we should be careful about running foul of our community’s homophobia. Painting South Asians as culturally homophobic ignores the role of racism in bolstering South Asian homophobia in the U.S. The pressures put on diasporic families by the spectre, even when unspoken, of American racism is at the heart of homophobia in this country. If you are afraid of your child being called Osama, being stopped by the police, being put into an ESL class because of the color of their skin, of course you more heavily police their gender and sexuality, because identifying as queer is seen as a privilege that we cannot afford to have. As Alok of Darkmatter put it, “homophobia is the diaspora’s response to racism,” not something inherent in South Asian cultures.

That reframing is important – that homophobia is actually a product of the U.S., and in particular a product of American racism. Once more, this is a project that every South Asian person in diaspora in the U.S. should be invested in, in a deeply personal way – by claiming queer legacies of what it means to be South Asian, we can reject portrayals of our communities as backwards and instead locate homophobia as American.

This doesn’t mean that we pretend that straight and gender conforming South Asians have the same investment in queer and trans* liberation, or that straight South Asians should claim queer spaces as their own because this is about them too. Instead, this means that non-queer and trans* South Asians are entering the struggle for queer and trans* liberation as their fight too, even as queer and trans* South Asians are given center stage, and as our voices are prioritized. This means that when we ask straight South Asian youth to join our fight, we speak to their self-interest too.

So again, what makes this ‘selfish solidarity’? We reframe challenging homophobia as challenging imperialism and the remnants of imperial laws, rewriting our own narratives of migration and community. So, standing in solidarity with us isn’t about taking the time to study and center our lives; rather, standing in solidarity with queer and trans* people is the only way to really craft an anti-imperial analysis of South Asia, and South Asians in the U.S. Without a queer and trans* liberation framework, South Asians, whether queer or not, remain seen as homophobic, backward, and colonized.

III. Selfish Solidarity in Organizing: APIs4BlackLives

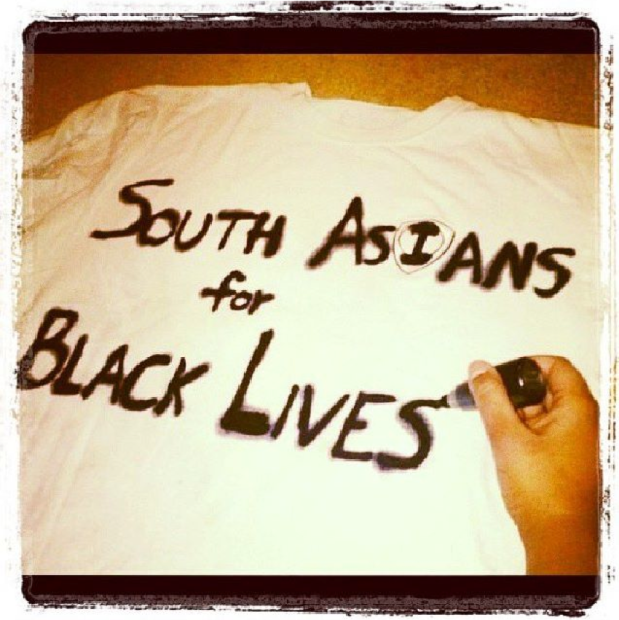

Now let’s talk about what ‘selfish solidarity’ can look like on the ground, as we organize our movements. I’m going to use as an example the recent APIs4BlackLives movement, that has sprung up in various cities across the U.S. in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement becoming nationally visible.

I’m going to go a little bit off topic and give some context for my own involvement with APIs4BlackLives, because I think it’s important to know. I am currently living in Madison, WI. On March 6th, Tony Robinson, an unarmed Black teenager, was murdered by police officer Matt Kenny, shot 5 times in the chest. If you’ve been following the news, Madison was suddenly on outlets across the country, on CNN, MSNBC, ABC News, and more; pictures of youth taking over the capital spread across social media; videos of protesters taking East Washington Ave. were everywhere.

That was and in many ways still is the moment of the whirlwind there, but it’s important to know that’s not where things began. Starting in November, a group called Young Gifted & Black (YGB) emerged as a coalition of young Black leaders across the city, many of whom identify as queer and/or gender non-conforming. This group emerged from decades of organizing in Black communities in Madison, and claimed that Madison is Ferguson, and in many ways is worse. In mid-January, we began talking about ways for Asians in Madison to visibly stand in solidarity with YGB, since many of us were friends with the organizers and consistently showing up at events. We decided to call ourselves Asians for Black Lives (recognizing that none of us identified as Pacific Islander) and have been working in solidarity in ways both visible – showing up at rallies, writing statements – and invisible – supporting our friends who are organizing, fundraising to create organizer care packages. The picture above is from Hmong youth at a city-wide school walkout.

Similarly, let’s be clear about the history of APIs4BlackLives nationwide. The existence of APIs4BlackLives is the result of years of political education in API and South Asian communities. Years of asking API people how we will leverage our racial privilege in this country to support Black communities, and other communities of color. How we will wield model minority status as a weapon against white supremacy, not against Blackness. Just as the Black Lives Matter movement has been organizing since the murder of Trayvon Martin, back in 2012. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders did not suddenly decide to rise up in solidarity with Black communities and against violence on Black bodies; that legacy has existed and has been intentionally built and bolstered for years.

In APIs4BlackLives spaces, solidarity is often framed as standing up for others. We say that we owe a debt to Black Americans, and that it’s time for us to repay that debt. And it’s true – we do. Our civil rights were earned on Black backs; the immigration laws that allow Asians into this country were passed through Black struggle. The 1965 Immigration Act drastically shifted the demographics and organizing context of Asians in the U.S., as Asians were suddenly allowed into the U.S. in large numbers, after a nearly complete ban in 1924. That act was passed due to the Civil Rights Movement. We do undoubtedly owe a debt.

And yet solidarity can’t stop there. Solidarity, if it is to be long-lasting and effective, can’t be framed as an overdue repayment, or simply the right thing to do. If we want to be in this fight for the long haul, we need to understand our own, personal investment in Black liberation and Black power.

So let’s be clear – I’m not suggesting that we demand to bring our voices to the table, that we stage a takeover of Black Lives Matter movements and spaces. I’m not suggesting that we center our own voices. Rather, I’m saying that we need to understand and frame our investment in Black liberation as deeply personal, and in fact, as life saving. We’re not in this for intellectual reasons; we’re in this because our lives do depend on Black freedom. We need to support because, as Alicia Garza wrote in A Herstory of the Black Lives Matter Movement, “When Black people get free, everybody gets free.”

Again, let’s explain with an example. Two days after the non-indictment of Darren Wilson, the officer who murdered Mike Brown, the Queer South Asian National Network put out a statement called A Week of Queer South Asian Rage. This was also the week that Obama’s Executive Action on immigration came out, leaving out many of our families and friends, so that’s part of the context here too. I’m going to read a piece of it, that highlights the personal investment South Asians in QSANN articulated in standing for and with Black Lives. From QSANN’s statement:

“Although we are also people of color in the U.S., our South Asian experiences of state violence vary greatly. As race, class and the model minority myth intertwine, many of us cannot understand the deep-seated fear of police shared by so many communities of color. And yet, depending on our access to wealth, immigration status, perceived religion, gender presentation, skin color, and more–many of us also experience state violence and police brutality regularly. We are stopped and frisked, beaten and bloodied, by the police. We continue to be surveilled, apprehended and deported, dealing with the onslaught of overt and covert Islamophobic attacks in a post-9/11 world. We fear for the safety and lives of our brothers, and our siblings, especially those who look darker, bearded and threatening. We fear that they too may be disappeared, beaten, taken. We know that their only crime is their perceived proximity to “terror” and to Blackness. Racism against us as South Asians does not exist in a vacuum; the racism we experience builds on long-standing systems of anti-Black racism and Islamophobia in the U.S. We know that our own liberation is inextricably bound to the struggle for Black lives and immigrant lives to matter in this country.”

In a post-9/11 world, where South Asians are increasingly racialized as brown and often as terrorist, we frame our solidarity as necessarily selfish, as an understanding that our liberations are deeply intertwined.

On February 6th, in Alabama, the need for deep and selfish investment of South Asians in Black Lives Matter movements became even more painfully and nationally clear. Sureshbhai Patel, recently arrived in the U.S. from India to help care for his grandson, was brutally slammed into the ground by a police officer, leaving him partially paralyzed. It is still unclear whether he will fully physically recover. The police were called on Mr. Patel because he was mistaken for “a skinny Black man;” he was brutalized, beaten to the point of literal paralysis but not killed, because he was understood to be Indian and immigrant. For South Asians in the U.S., when we are willing to admit it, this is what’s at stake – we may survive our encounters with the police, which is a real privilege, but ending up alive and brutalized will never be enough.

In response to Mr. Patel’s brutalization by the police, Deepa Iyer and Subhash Kateel wrote an article in India Abroad titled, So that all our grandparents walk freely. They write: “When young African American youth say #Blacklivesmatter, we must say it with them. When Black lives actually matter in America, our lives and our families’ lives will matter as well. And then maybe, all of our grandfathers can take a walk down the street without fear and in peace.”

That’s at the crux of South Asians for Black Lives. This is where our desire for liberation needs to come from. Sure, we’re in this work to support our friends, our fam; to repay our historical debt; but also because we understand that if Black people are able to walk down the street without being afraid, we will be able to do the same. We understand that while Black liberation is not “our” struggle, we will always win when Black people win, and feel safer when Black people feel safer. By framing our solidarity as selfish, and this fight as one that our lives depend on though it’s not ours to lead, hopefully this coalition-building will become more sustainable.

Specifically, this idea of ‘selfish solidarity’ around #BlackLivesMatter is an organizing strategy for South Asian spaces in this example, or non-Black spaces more generally. Again, because it does bear repeating in this political moment, this doesn’t mean that we cry South Asian Lives Matter too, or any other version of [Insert Here] Lives Matter. That’s not solidarity at all.

What “selfish solidarity” does mean is that when I call my mother the day after Darren Wilson’s non-indictment, I ask her if she’s been watching the news, and then I ask her if she worries about my little brother. Who is taller than I am, and just darker-skinned enough for me to worry. She admits that yes, she does worry. And as story after story have captured national attention, we worry more. That’s the entry point for organizing in South Asian communities around Black Lives Matter. That’s how you keep people who are not organizers, have no desire to be activists, will even tell you that they don’t do politics – people like my mom – that’s how we have to frame this movement and this moment, selfishly, to convince our people that this is in fact deeply about them and their loved ones, even as Black lives are the most at stake, and as Black voices need to be centered.

Part of “selfish solidarity” is also understanding and using our own privileges. Asian Americans and South Asians undoubtedly wield racial privilege in this country, in comparison to other communities of color. And that’s why we even need this frame of “selfish solidarity” – because there are plenty of Asian Americans, including South Asians, who would prefer to ride out our racial privilege, instead of locating and acknowledging our lived stake in this struggle. The model minority myth is still real.

In Madison, going back to where I’m currently living, that selfish solidarity and acknowledgement of privilege has looked like a lot of things: corralling financial resources, for those of us who have them or know people who do; writing, because Madison is an academic city and Asian people, faces and names are often seen as more ‘credible’ than Black voices; showing up at rallies and protests and doing whatever’s asked; interfacing with police, knowing that we’re less likely to end up dead for doing so, especially in front of a crowd. We are figuring out how to use our privilege across the country – both because it’s the right thing to do, and also because we know that our lives and our safety depend on it.

This is where I’ve often found the framing of APIs4BlackLives lacking, and where centering South Asian, Southeast Asian and Pacific Islander voices changes the conversation. If we really talked about the lived investment we have in Black liberation; if we centered the racialized experiences of South Asians, Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders; our call for solidarity would look different. We would show up for ourselves, as much as for an idea of solidarity. This is a strategy of organizing that doesn’t center our own lives, which is what we’re often told organizing is about, but rather builds our deeply personal investment in showing up for struggles and movements led by Black people and ultimately builds our collective strength in deeper and more lasting ways. This is how APIs4BlackLives becomes a sustainable coalition, and not a flash in the pan moment.

IV. Conclusion

To close out, I want to talk a little bit about why I called this ‘selfish’ solidarity. It’s uncomfortable to say and to hear – right? A friend of mine suggested ‘survival solidarity’ instead. And while I like that term more in some ways, it also feels too easy. I kept ‘selfish solidarity’ because it is uncomfortable. And even when solidarity feels deeply personal, and self-interested, and has the commitment of your whole self – it should feel uncomfortable. Solidarity isn’t a destination. You don’t ever happily arrive at solidarity. We should always be asking and questioning if we’re doing the right things, supporting in the right ways.

Bernice Johnson Reagon, who is often credited with being the musical soul of the Civil Rights Movement, argued that we need to recognize the difference between coalition and home. Solidarity and coalition aren’t the same, but the sentiment translates. In her piece Coalition Politics: Turning the Century, she said: “Coalition work is not work done in your home. Coalition work has to be done in the streets. And it is some of the most dangerous work you can do. And you shouldn’t look for comfort. Some people will come to a coalition and they rate the success of the coalition on whether or not they feel good when they get there. They’re not looking for a coalition; they’re looking for a home!”

I think that’s an important thing to remember as we close out – coalition is not home. Even if solidarity is selfish, coalition should be and feel uncomfortable. If solidarity, even ‘selfish solidarity’ starts to feel comfortable, that might be a sign that we’ve moved away from our goals.

Hi!

I’m Michon from The Body is Not An Apology. We would love to crosspost a version of this! Please let me know!

hey, so sorry this is delayed. I would love that! you can email me at tospeakasong@gmail.com if you need more info 🙂

Excellent! Thank you!